Jason Sizemore and Lesley Connor (eds.), Apex Magazine 2021: The Companion Anthology. Apex Book Company, 2022. Pp. 544. ISBN 978-1-955765-06-0. $27.95 pb/$8.99 e.

Reviewed by Christina De La Rocha

Apex Magazine 2021: The Companion Anthology serves up 48 stories originally published in Apex Magazine in issues 121–128, representing the year the publication bounced back from a brief hiatus. Buying a copy, in either paperback or digital form, is a great way to support an award-winning speculative fiction magazine whose issues are otherwise free to read at the magazine’s website. On the upside, the stories are of generally high quality and come from authors from a variety of places around the world. One entire issue included in the anthology was devoted to Indigenous authors telling speculative fiction stories with Indigenous protagonists—a definite breath of fresh air. But, reader, I warn you, at 544 pages (or 626 if you include front and back matter), the anthology is a long slog through darkness. It's definitely not an anthology built for binge-reading.

Apex Magazine 2021: The Companion Anthology serves up 48 stories originally published in Apex Magazine in issues 121–128, representing the year the publication bounced back from a brief hiatus. Buying a copy, in either paperback or digital form, is a great way to support an award-winning speculative fiction magazine whose issues are otherwise free to read at the magazine’s website. On the upside, the stories are of generally high quality and come from authors from a variety of places around the world. One entire issue included in the anthology was devoted to Indigenous authors telling speculative fiction stories with Indigenous protagonists—a definite breath of fresh air. But, reader, I warn you, at 544 pages (or 626 if you include front and back matter), the anthology is a long slog through darkness. It's definitely not an anthology built for binge-reading.

Rachel Rosen’s Cascade is the first book of a trilogy, The Sleep of Reason, alluding to Goya’s etching of the same title, in which a young man is sleeping on his desk and swarms of bats, owls, and other denizens of the dark flock towards him—or is it from his dreaming brain? The titular Cascade refers to the major cataclysmic shift that has occurred an indefinite period before the novel’s start, resulting in weird occurrences, like cracks appearing in the surface of the earth, people being transformed into demons, the sprouting of “shriekgrass” to replace edible crops, and the general appearance of magic. As one major character, a wizard, puts it, the question is not what can we do to preserve our way of life, but what does magic want?

Rachel Rosen’s Cascade is the first book of a trilogy, The Sleep of Reason, alluding to Goya’s etching of the same title, in which a young man is sleeping on his desk and swarms of bats, owls, and other denizens of the dark flock towards him—or is it from his dreaming brain? The titular Cascade refers to the major cataclysmic shift that has occurred an indefinite period before the novel’s start, resulting in weird occurrences, like cracks appearing in the surface of the earth, people being transformed into demons, the sprouting of “shriekgrass” to replace edible crops, and the general appearance of magic. As one major character, a wizard, puts it, the question is not what can we do to preserve our way of life, but what does magic want? Strange Horizons’ November issues have a lot to say, and in them, I saw a reflection of much happening in the world today, from the climate crisis to the digital world, monsters and magic and far-away planets. Stories and poems about communities standing together, of breaking free of what chains us, of creating a better world for those to come (including ourselves); these issues really resonated with me.

Strange Horizons’ November issues have a lot to say, and in them, I saw a reflection of much happening in the world today, from the climate crisis to the digital world, monsters and magic and far-away planets. Stories and poems about communities standing together, of breaking free of what chains us, of creating a better world for those to come (including ourselves); these issues really resonated with me. When Hungry Shadow Press announced It Was All a Dream, I was immediately curious and a bit puzzled. The foremost question in my mind: What does it mean to do a trope right? There are many possible answers to this question, and It Was All a Dream showcases all of them. The stories in this anthology fall into four categories: Parodies, metanarratives, inversions, and stories that are played straight. Quite an assortment!

When Hungry Shadow Press announced It Was All a Dream, I was immediately curious and a bit puzzled. The foremost question in my mind: What does it mean to do a trope right? There are many possible answers to this question, and It Was All a Dream showcases all of them. The stories in this anthology fall into four categories: Parodies, metanarratives, inversions, and stories that are played straight. Quite an assortment! I am acutely aware that I approach every book I read weighed-down by the baggage of my history. That load was particularly burdensome as I read the excellent Barzakh: The Land In-Between by Moussa Ould Ebnou. My exposure to African literature is woefully inadequate, so I can’t place this book anywhere within that tradition. I can’t tell you how it stacks up against contemporary African literature, or the African literature of the past. I can tell that my unfamiliarity with Africa as a literary tradition and as a geographic region heightened the sense of strangeness and other-ness I felt while reading. In many ways, that actually impacted my experience with this novel for the better. Readers who are more familiar with these traditions are sure to appreciate what they find in this story.

I am acutely aware that I approach every book I read weighed-down by the baggage of my history. That load was particularly burdensome as I read the excellent Barzakh: The Land In-Between by Moussa Ould Ebnou. My exposure to African literature is woefully inadequate, so I can’t place this book anywhere within that tradition. I can’t tell you how it stacks up against contemporary African literature, or the African literature of the past. I can tell that my unfamiliarity with Africa as a literary tradition and as a geographic region heightened the sense of strangeness and other-ness I felt while reading. In many ways, that actually impacted my experience with this novel for the better. Readers who are more familiar with these traditions are sure to appreciate what they find in this story. When I first encountered the work of adrienne marie brown, it was through her book, Emergent Strategy. That book showed me a gap in my existence and began the process of filling it in. brown introduced to me the concept of moving through systems in nonlinear and creative ways with whole minds, bodies, and communities. She embraces this perspective again in her new release, Fables and Spells: Collected and New Short Fiction and Poetry. The book is long and complex, ever-shifting like an octopus exploring the environment. It challenges the reader to find a place of relaxed alertness while acknowledging the pain of both change and stagnancy. brown is one of the few writers who makes the reader inescapably aware of the body—not just the reader’s body, but all bodies in space and time and politics. Her work and activism are tender and confident like a practiced lover, alive and breathing.

When I first encountered the work of adrienne marie brown, it was through her book, Emergent Strategy. That book showed me a gap in my existence and began the process of filling it in. brown introduced to me the concept of moving through systems in nonlinear and creative ways with whole minds, bodies, and communities. She embraces this perspective again in her new release, Fables and Spells: Collected and New Short Fiction and Poetry. The book is long and complex, ever-shifting like an octopus exploring the environment. It challenges the reader to find a place of relaxed alertness while acknowledging the pain of both change and stagnancy. brown is one of the few writers who makes the reader inescapably aware of the body—not just the reader’s body, but all bodies in space and time and politics. Her work and activism are tender and confident like a practiced lover, alive and breathing. The Dark is a monthly online zine famous for both its excellent dark fiction output and its stringent and remarkably rapid rejections—indeed, while I was working on this review a tweet went somewhat viral from an author irate that they had rejected his manuscript three minutes after he submitted it. It’s a leading venue for modern horror fiction that favors atmosphere over gore, and provides a home both for the big names of the genre and relative newcomers. All four stories in the September 2022 issue are strong entries. Stylistically, they share a clear, realist voice, with rather straightforward narratives. There are flashbacks, and the smartly-paced unveiling of details necessary for the genre, but none are overly experimental or knotty in approach.

The Dark is a monthly online zine famous for both its excellent dark fiction output and its stringent and remarkably rapid rejections—indeed, while I was working on this review a tweet went somewhat viral from an author irate that they had rejected his manuscript three minutes after he submitted it. It’s a leading venue for modern horror fiction that favors atmosphere over gore, and provides a home both for the big names of the genre and relative newcomers. All four stories in the September 2022 issue are strong entries. Stylistically, they share a clear, realist voice, with rather straightforward narratives. There are flashbacks, and the smartly-paced unveiling of details necessary for the genre, but none are overly experimental or knotty in approach. The story begins in a gambling joint in Goetia, a mining town in the mountains run by a privileged elite. It’s an unholy place and Celeste, a dealer at the card tables of the Eden, “Perdition Street’s premiere gambling and drinking establishment,” has seen her share of squalor, degradation, and exploitation and there’s the obligatory saloon-fight in the first ten pages. But when her sister Mariel, a singer at the Eden, is arrested for a particularly nasty murder, Celeste is forced to embark upon a quest to prove her sister’s innocence. In doing so, she sees even more of the town’s darker side than she ever thought existed.

The story begins in a gambling joint in Goetia, a mining town in the mountains run by a privileged elite. It’s an unholy place and Celeste, a dealer at the card tables of the Eden, “Perdition Street’s premiere gambling and drinking establishment,” has seen her share of squalor, degradation, and exploitation and there’s the obligatory saloon-fight in the first ten pages. But when her sister Mariel, a singer at the Eden, is arrested for a particularly nasty murder, Celeste is forced to embark upon a quest to prove her sister’s innocence. In doing so, she sees even more of the town’s darker side than she ever thought existed. The 22nd issue of Polar Borealis, a publication I was until now unfamiliar with, opens with an editorial, musing on how far this Aurora-award winning publication has come in the six-plus years since its inception. Read all over the world, nominated for and winning awards, a paying market for Canadian writers and artists, while still acknowledging how challenging the industry can be. Overall, it’s cheerful and optimistic; hopeful, with an eye on the future.

The 22nd issue of Polar Borealis, a publication I was until now unfamiliar with, opens with an editorial, musing on how far this Aurora-award winning publication has come in the six-plus years since its inception. Read all over the world, nominated for and winning awards, a paying market for Canadian writers and artists, while still acknowledging how challenging the industry can be. Overall, it’s cheerful and optimistic; hopeful, with an eye on the future. Novelettes and novellas, the red-headed stepchildren of the book world. Too long to place in a magazine and uneconomical to publish on their own, they languish on hard drives, making an occasional appearance as the flagship piece in a single-author collection, but otherwise neglected. Which is a shame, because they’re my fictional first love. About the same length as a TV episode or a graphic novel, they’re a lean, focused form of storytelling, just the right length to fully explore a single arc without needing to detour into subplots. They’re a convenient airport-or-dentist size and they’re nice for those of us who have a bad track record of finishing full-length novels.

Novelettes and novellas, the red-headed stepchildren of the book world. Too long to place in a magazine and uneconomical to publish on their own, they languish on hard drives, making an occasional appearance as the flagship piece in a single-author collection, but otherwise neglected. Which is a shame, because they’re my fictional first love. About the same length as a TV episode or a graphic novel, they’re a lean, focused form of storytelling, just the right length to fully explore a single arc without needing to detour into subplots. They’re a convenient airport-or-dentist size and they’re nice for those of us who have a bad track record of finishing full-length novels. If you tried to reverse engineer the contents of Issue 363 of the literary adventure fantasy online magazine Beneath Ceaseless Skies, you might find a writing prompt in your hand: tell a tale of thwarted immortality. That probably isn’t actually the origin of the two new stories published in the issue, of course. It’s more likely that an editor decided that these two new stories belonged together because of that similarity at their core. Either way, what’s interesting is that these two new stories taking thwarted immortality as a premise are nothing like each other.

If you tried to reverse engineer the contents of Issue 363 of the literary adventure fantasy online magazine Beneath Ceaseless Skies, you might find a writing prompt in your hand: tell a tale of thwarted immortality. That probably isn’t actually the origin of the two new stories published in the issue, of course. It’s more likely that an editor decided that these two new stories belonged together because of that similarity at their core. Either way, what’s interesting is that these two new stories taking thwarted immortality as a premise are nothing like each other. Fireside Magazine was—and, yes, I must sadly say was—a online publisher of short stories, poems, and novels. Founded in 2012, it’s had a respectable 10-year run, at first based on crowdfunding, then on subscriptions. But now Fireside’s operations are now winding down. Issue 103 (Summer 2022) represents the magazine’s final offering of stories to the world.

Fireside Magazine was—and, yes, I must sadly say was—a online publisher of short stories, poems, and novels. Founded in 2012, it’s had a respectable 10-year run, at first based on crowdfunding, then on subscriptions. But now Fireside’s operations are now winding down. Issue 103 (Summer 2022) represents the magazine’s final offering of stories to the world.

Confession time: I wanted to submit to this one, but something came up, where “something” is “my own laziness.” But, having read it, I’m now glad I didn’t submit, because I probably would have dragged down the average. When Speculatively Queer launched last year with the triumphant It Gets Even Better: Stories of Queer Possibility, it stepped into an under-served market: Full-length queer SFF short stories. Consequently, a lot of us have been keeping an eye on it. Xenocultivars, its sophomore publication, is a very strong follow-up, and a sign that Speculatively Queer may be a formidable new contender.

Confession time: I wanted to submit to this one, but something came up, where “something” is “my own laziness.” But, having read it, I’m now glad I didn’t submit, because I probably would have dragged down the average. When Speculatively Queer launched last year with the triumphant It Gets Even Better: Stories of Queer Possibility, it stepped into an under-served market: Full-length queer SFF short stories. Consequently, a lot of us have been keeping an eye on it. Xenocultivars, its sophomore publication, is a very strong follow-up, and a sign that Speculatively Queer may be a formidable new contender. A reader’s response to In Days to Come, Lisa Timpf’s slim collection of poetry, will depend on his or her attitude toward a few things:

A reader’s response to In Days to Come, Lisa Timpf’s slim collection of poetry, will depend on his or her attitude toward a few things: Sein und Werden, per their onsite manifesto, is a quarterly online and occasional print journal whose goal is to invoke Werdenism, a term coined by the editor to encompass her modern aesthetic vision of “being and becoming” taken from the Expressionists. Each issue is themed, and this one starts with a prompt of “If I were you…” This is carried cutely by the home page where you are directed to a choice between two arrows: content or contributors. The overarching or underlying philosophy of the works chosen revolve around Existentialism, Surrealism, and Expressionism.

Sein und Werden, per their onsite manifesto, is a quarterly online and occasional print journal whose goal is to invoke Werdenism, a term coined by the editor to encompass her modern aesthetic vision of “being and becoming” taken from the Expressionists. Each issue is themed, and this one starts with a prompt of “If I were you…” This is carried cutely by the home page where you are directed to a choice between two arrows: content or contributors. The overarching or underlying philosophy of the works chosen revolve around Existentialism, Surrealism, and Expressionism. Mithila Review, founded in 2015, is a science fiction and fantasy magazine based in India but international in scope. This is a promise Mithila absolutely delivers on, for not only does it contain stories from all over, the magazine’s own gaze looks firmly out from its non-Western corner of the world and this is a wonderful thing. About half of the stories in the magazine are told from an Indian perspective and it’s a delight to read the stories that look out at the future and the effects of global events through the eyes, hearts, and experiences of people and places many of us are not used to inhabiting in fiction, given the Anglosphere’s publishing industry’s gatekeeping in favor of white, Western authors. It helps that the stories, articles, and poems in Mithila Review lean into the literary and are written handsomely and at times in an English that is perfect yet non-Western in tone. This deepens the flavor of these works and befits a magazine that is named for a distinct geographic, cultural, and linguistic region with ancient roots that is now split by the border between India and Nepal and grappling with attempts at political control and cultural and linguistic assimilation from two different countries.

Mithila Review, founded in 2015, is a science fiction and fantasy magazine based in India but international in scope. This is a promise Mithila absolutely delivers on, for not only does it contain stories from all over, the magazine’s own gaze looks firmly out from its non-Western corner of the world and this is a wonderful thing. About half of the stories in the magazine are told from an Indian perspective and it’s a delight to read the stories that look out at the future and the effects of global events through the eyes, hearts, and experiences of people and places many of us are not used to inhabiting in fiction, given the Anglosphere’s publishing industry’s gatekeeping in favor of white, Western authors. It helps that the stories, articles, and poems in Mithila Review lean into the literary and are written handsomely and at times in an English that is perfect yet non-Western in tone. This deepens the flavor of these works and befits a magazine that is named for a distinct geographic, cultural, and linguistic region with ancient roots that is now split by the border between India and Nepal and grappling with attempts at political control and cultural and linguistic assimilation from two different countries. In an episode of her podcast Live Like the World Is Dying, Margaret Killjoy reframes the concept of eco-nihilism as something that creates room for personal agency amid the inevitability of climate change. If we embrace the fact that climate change is already here, and that we cannot prevent all the horrors ahead, does this not lighten our burden as individuals? Are we not then freed up to focus on what we can do and save, instead of trying to do and save it all?

In an episode of her podcast Live Like the World Is Dying, Margaret Killjoy reframes the concept of eco-nihilism as something that creates room for personal agency amid the inevitability of climate change. If we embrace the fact that climate change is already here, and that we cannot prevent all the horrors ahead, does this not lighten our burden as individuals? Are we not then freed up to focus on what we can do and save, instead of trying to do and save it all? Michael McCarty has published dozens of books, especially non-fiction work about genre writers and artists. Crystal Lake Publishing is a relative newcomer, but they’ve already started distinguishing themselves by having a good eye for talent and publishing books that enhance the horror and science fiction community. More Modern Mythmakers is a strong collection of interviews that are a testament to McCarty’s access and eye, and the book would make a nice addition to your shelf, but it has some shortcomings that make it less than completely successful for a book of its kind.

Michael McCarty has published dozens of books, especially non-fiction work about genre writers and artists. Crystal Lake Publishing is a relative newcomer, but they’ve already started distinguishing themselves by having a good eye for talent and publishing books that enhance the horror and science fiction community. More Modern Mythmakers is a strong collection of interviews that are a testament to McCarty’s access and eye, and the book would make a nice addition to your shelf, but it has some shortcomings that make it less than completely successful for a book of its kind..jpeg) Neptune Frost, a mystical sci-fi musical set in Burundi and filmed in Rwanda, is the creation of codirectors Saul Williams (a songwriter and poet) and Anisia Uzeyman (a director and actor). It draws on Williams’s albums Martyr Loser King (2016) and Encrypted and Vulnerable (2019) and was financed via a 2018 Kickstarter campaign.

Neptune Frost, a mystical sci-fi musical set in Burundi and filmed in Rwanda, is the creation of codirectors Saul Williams (a songwriter and poet) and Anisia Uzeyman (a director and actor). It draws on Williams’s albums Martyr Loser King (2016) and Encrypted and Vulnerable (2019) and was financed via a 2018 Kickstarter campaign. There’s a freewheeling energy to the introductions to El Porvenir, ¡Ya!, a 2022 Chicano science fiction anthology edited by Scott Russel Duncan, Armando Rendón, and Jenny Irizary. Both pieces, one by Ernest Hogan and one by Duncan(-Fernandez), proclaim with great celebratory fanfare the distinct possibilities and resurgence of the “Latinoid imagination” in contemporary science fiction. The absence of Latino rep in preceding sci-fi did not escape these editors’ notice, either, and the collection promises to introduce characters and contexts that illustrate the science-fictional nature of existence already intrinsic to many Latino communities living in blended, mestizo realities, especially in North America. How can there not be worth in celebrating, discovering, and cultivating as many of their imagined futures as possible?

There’s a freewheeling energy to the introductions to El Porvenir, ¡Ya!, a 2022 Chicano science fiction anthology edited by Scott Russel Duncan, Armando Rendón, and Jenny Irizary. Both pieces, one by Ernest Hogan and one by Duncan(-Fernandez), proclaim with great celebratory fanfare the distinct possibilities and resurgence of the “Latinoid imagination” in contemporary science fiction. The absence of Latino rep in preceding sci-fi did not escape these editors’ notice, either, and the collection promises to introduce characters and contexts that illustrate the science-fictional nature of existence already intrinsic to many Latino communities living in blended, mestizo realities, especially in North America. How can there not be worth in celebrating, discovering, and cultivating as many of their imagined futures as possible? As a Canadian, coming to England has been an interesting experience. Much of Canada’s history prior to the arrival of the European settlers has been forgotten or deliberately lost. So coming to a country where we can walk freely through Neolithic ruins and 2000 year old Roman coins are routinely dug from the river mud is… odd. It is a place that is rife with mystery and secrets—and the potential for horror.

As a Canadian, coming to England has been an interesting experience. Much of Canada’s history prior to the arrival of the European settlers has been forgotten or deliberately lost. So coming to a country where we can walk freely through Neolithic ruins and 2000 year old Roman coins are routinely dug from the river mud is… odd. It is a place that is rife with mystery and secrets—and the potential for horror. The April “2k22” issue, entitled “Experimental Realms,” completes the second full year of publication of Penumbric following a fifteen-year hiatus. “Experimental Realms” is also one of Penumbric magazine’s roughly annual special “art and prose” issues. There is certainly no shortage of either (plus poetry) in the issue; 78 numbered pages thick, it features nine speculative fiction tales, six poems, and, including the cover, seven works of art as well as panels and notes relating to the webcomic Mondo Mecho.

The April “2k22” issue, entitled “Experimental Realms,” completes the second full year of publication of Penumbric following a fifteen-year hiatus. “Experimental Realms” is also one of Penumbric magazine’s roughly annual special “art and prose” issues. There is certainly no shortage of either (plus poetry) in the issue; 78 numbered pages thick, it features nine speculative fiction tales, six poems, and, including the cover, seven works of art as well as panels and notes relating to the webcomic Mondo Mecho. “Archives” is a surprisingly bendy term these days, currently popular as an academic theory of textual collection and collation that has staggeringly little to do with the reality of physical materials hosted in libraries, records offices, and various institutions. As an actual archivist who spends real time up to her elbows in odds and ends in various levels of process, it’s a topic I can get a bit cranky about. E. Saxey, author of Lost in the Archives, is a queer academic who clearly knows the feeling; their debut collection spans the past, present, and future, this plane and other planes, and gracefully and effortlessly bounces between soft romance, cynical academia, and both hope and pessimism for our cloudy future.

“Archives” is a surprisingly bendy term these days, currently popular as an academic theory of textual collection and collation that has staggeringly little to do with the reality of physical materials hosted in libraries, records offices, and various institutions. As an actual archivist who spends real time up to her elbows in odds and ends in various levels of process, it’s a topic I can get a bit cranky about. E. Saxey, author of Lost in the Archives, is a queer academic who clearly knows the feeling; their debut collection spans the past, present, and future, this plane and other planes, and gracefully and effortlessly bounces between soft romance, cynical academia, and both hope and pessimism for our cloudy future. The best part of fairy tales for me isn’t the reversal of fortunes or the justice delivered. For me, it’s always been the slantwise magic that follows rules we can’t see—an early form of magical realism wherein the burdened and despairing characters find relief. This wild magic often arrived in the form of a fairy godmother, subverting the ill-fated mothers and scary stepmothers sprinkled like blood stains over the pages. The fairy godmother feels deserved and arbitrary at the same time, allowing a reader centuries in the future to believe that they, too, might one day be magicked into a gorgeous gown and a happily ever after. And as Wolford points out in her introduction, “many people transform our lives with simple generosity and kindness.” We all have that magic within us.

The best part of fairy tales for me isn’t the reversal of fortunes or the justice delivered. For me, it’s always been the slantwise magic that follows rules we can’t see—an early form of magical realism wherein the burdened and despairing characters find relief. This wild magic often arrived in the form of a fairy godmother, subverting the ill-fated mothers and scary stepmothers sprinkled like blood stains over the pages. The fairy godmother feels deserved and arbitrary at the same time, allowing a reader centuries in the future to believe that they, too, might one day be magicked into a gorgeous gown and a happily ever after. And as Wolford points out in her introduction, “many people transform our lives with simple generosity and kindness.” We all have that magic within us. Mythaxis Magazine, if you haven’t previously had the pleasure, is currently a quarterly online magazine of speculative fiction that feels like a glimpse into the internet we could have had, had we not allowed it to turn into a virtual shopping mall, a brewer of bullying, and a weaponized spreader of disinformation. Free to read and free from advertisements, Mythaxis is a labor of love that will take you strange places and feed you amazing ideas just because excellence is an excellent endeavor. The stories that Mythaxis serves as a portal to are exactly the sorts of stories you hope you would be true enough to your ideals to produce, if you had that kind of talent. Or, at least that’s how it feels to me. People with talent should be doing great things with it, not just the same old thing, averagely, already done by everyone else.

Mythaxis Magazine, if you haven’t previously had the pleasure, is currently a quarterly online magazine of speculative fiction that feels like a glimpse into the internet we could have had, had we not allowed it to turn into a virtual shopping mall, a brewer of bullying, and a weaponized spreader of disinformation. Free to read and free from advertisements, Mythaxis is a labor of love that will take you strange places and feed you amazing ideas just because excellence is an excellent endeavor. The stories that Mythaxis serves as a portal to are exactly the sorts of stories you hope you would be true enough to your ideals to produce, if you had that kind of talent. Or, at least that’s how it feels to me. People with talent should be doing great things with it, not just the same old thing, averagely, already done by everyone else. Veronica G. Henry is not from New Orleans and does not practice Vodou, but she consulted experts for both, and this careful consideration shines in details and authorial voice in her mystery novel The Quarter Storm. Unlike many past representations of Vodou, Henry focuses on the history and faith, and leaves the fetishization behind. This second book is a departure for Henry from the dark fantasy of an evil carnival, and instead brings characters who could easily be found during a walk through your city, and a murder that feels ripped from the headlines. (I originally assumed this book was self-published due to the surprisingly neutral and forgettable cover for the ebook; 47North turns out to be an imprint of Amazon Publishing, and they offer their acquistions through Kindle Unlimited—which is how I found it—as well as paperback and audio editions.)

Veronica G. Henry is not from New Orleans and does not practice Vodou, but she consulted experts for both, and this careful consideration shines in details and authorial voice in her mystery novel The Quarter Storm. Unlike many past representations of Vodou, Henry focuses on the history and faith, and leaves the fetishization behind. This second book is a departure for Henry from the dark fantasy of an evil carnival, and instead brings characters who could easily be found during a walk through your city, and a murder that feels ripped from the headlines. (I originally assumed this book was self-published due to the surprisingly neutral and forgettable cover for the ebook; 47North turns out to be an imprint of Amazon Publishing, and they offer their acquistions through Kindle Unlimited—which is how I found it—as well as paperback and audio editions.) At least one lifetime ago, I took a graduate class covering rhetoric and technology. It was a great class with a great professor and classmates whose company I enjoyed. One evening we were discussing the ability of technology to track us, and I mentioned my frequent customer fob for the gas station I frequented. I hadn’t thought of it before, I said, but a so-inclined Speedway marketing manager would have been able to figure out an awful lot about me based on what I bought at each station I visited. About where I lived. About where I visited. How many kids I had and their approximate ages (because who in their right mind buys four slushies at one time?). What days I attended class. The approximate day the doctor told me to stop drinking slushies. A general idea of what kind of car I drove. It was a scary reminder of all the information I happily turned over just to earn a free slushie after every fifth purchase.

At least one lifetime ago, I took a graduate class covering rhetoric and technology. It was a great class with a great professor and classmates whose company I enjoyed. One evening we were discussing the ability of technology to track us, and I mentioned my frequent customer fob for the gas station I frequented. I hadn’t thought of it before, I said, but a so-inclined Speedway marketing manager would have been able to figure out an awful lot about me based on what I bought at each station I visited. About where I lived. About where I visited. How many kids I had and their approximate ages (because who in their right mind buys four slushies at one time?). What days I attended class. The approximate day the doctor told me to stop drinking slushies. A general idea of what kind of car I drove. It was a scary reminder of all the information I happily turned over just to earn a free slushie after every fifth purchase. Sharon Powell’s novel The Shadow is idiosyncratic. That it is in the tradition of Frankenstein literature is evident from the name of the central character, Victor Frankenstein. This Frankenstein is a doctor who dissects corpses, but upon finding a young man who has been buried by an avalanche and cryonically preserved, he keeps the young man in the best cold storage possible in early 19th-century central Europe. In overseeing his living but unconscious body, the doctor is surprised by a spiritual visitation: the spirit of the frozen young man appears above the gurney and addresses him, involving the doctor in a plot to rescue a group of children who are “cared for” by one of the most respected men of the village, but who, according to the spirit, has possession of this group of orphans and, in a Dickensian twist, is working them to death. Simon, the spirit, and the doctor team up to locate the orphans to free them, and ultimately bring their tormentor to justice.

Sharon Powell’s novel The Shadow is idiosyncratic. That it is in the tradition of Frankenstein literature is evident from the name of the central character, Victor Frankenstein. This Frankenstein is a doctor who dissects corpses, but upon finding a young man who has been buried by an avalanche and cryonically preserved, he keeps the young man in the best cold storage possible in early 19th-century central Europe. In overseeing his living but unconscious body, the doctor is surprised by a spiritual visitation: the spirit of the frozen young man appears above the gurney and addresses him, involving the doctor in a plot to rescue a group of children who are “cared for” by one of the most respected men of the village, but who, according to the spirit, has possession of this group of orphans and, in a Dickensian twist, is working them to death. Simon, the spirit, and the doctor team up to locate the orphans to free them, and ultimately bring their tormentor to justice.

Omenana, the now-quarterly bilingual publication (English and French) of African and African diaspora SFF is still going strong with issue 20. The name of the publication is Igbo for both divinity and culture, and speaks to the speculative that permeates African histories, folklore, spirituality, and future-dreaming. As continental African writers show up more in Western SFF, it’s easy to overlook the key role of local African publications, especially as incubators for experimentation and new voices—but it matters immensely. The four-person editorial team of Omenana is Nigerian, with one member living in Canadian diaspora, and although they can only offer token payments for now, you can invest in their

Omenana, the now-quarterly bilingual publication (English and French) of African and African diaspora SFF is still going strong with issue 20. The name of the publication is Igbo for both divinity and culture, and speaks to the speculative that permeates African histories, folklore, spirituality, and future-dreaming. As continental African writers show up more in Western SFF, it’s easy to overlook the key role of local African publications, especially as incubators for experimentation and new voices—but it matters immensely. The four-person editorial team of Omenana is Nigerian, with one member living in Canadian diaspora, and although they can only offer token payments for now, you can invest in their  There is an art to creating a “Best of” list, whether that be a “Best of Shakespeare’s Plays” or “Best Singles by Take That.” You are inevitably going to make a lot of people angry. Art and tastes are subjective, and one man’s trash is another person’s treasure. And nowhere is this more true than with horror fiction. Fears are as individual as fingerprints. The film or book that terrify us and make chills run down our spine might make be utterly dull to another. And we horror fans are desperately protective of our best beloveds. I have seen knock-down drag-out fights between fans who can’t agree whether Matthew Stokoe’s Cows is trash or a masterpiece. So creating a volume in which you want to compile the best of modern horror fiction is a bit of a risky endeavour. Fortunately for all of us, Alessandro Manzetti decided to take on the challenge, and he took it on with grace, courage, and a library I can only dream of possessing.

There is an art to creating a “Best of” list, whether that be a “Best of Shakespeare’s Plays” or “Best Singles by Take That.” You are inevitably going to make a lot of people angry. Art and tastes are subjective, and one man’s trash is another person’s treasure. And nowhere is this more true than with horror fiction. Fears are as individual as fingerprints. The film or book that terrify us and make chills run down our spine might make be utterly dull to another. And we horror fans are desperately protective of our best beloveds. I have seen knock-down drag-out fights between fans who can’t agree whether Matthew Stokoe’s Cows is trash or a masterpiece. So creating a volume in which you want to compile the best of modern horror fiction is a bit of a risky endeavour. Fortunately for all of us, Alessandro Manzetti decided to take on the challenge, and he took it on with grace, courage, and a library I can only dream of possessing. Sometimes an anthology is just a really good excuse to sit with strong and wide-ranging storytelling. Such was certainly the case with The Reinvented Heart, a collection of 24 stories centered on a wide range of emotional bonds, challenges, and opportunities. Across the board, the writing was deft and immersive, the stories were distinct and memorable, and many worked in striking conversation with their neighbours. The organization of this collection into three overarching “movements”—”Hearts,” “Hands,” and “Minds,” each opening with a small but potent bit of poetry by Jane Yolen, and revealing plenty of resonant story placements—also makes for an excellently curated reading experience, best read in the provided order. My only caveat, before I leap into high praise for the pieces themselves, is that I don’t think all of these stories reflect the anthology’s explicit mission statement. Then again, an anthology is often expected to carve out a singular role for itself in the market, and promotional material often makes sweeping claims to bring readers in.

Sometimes an anthology is just a really good excuse to sit with strong and wide-ranging storytelling. Such was certainly the case with The Reinvented Heart, a collection of 24 stories centered on a wide range of emotional bonds, challenges, and opportunities. Across the board, the writing was deft and immersive, the stories were distinct and memorable, and many worked in striking conversation with their neighbours. The organization of this collection into three overarching “movements”—”Hearts,” “Hands,” and “Minds,” each opening with a small but potent bit of poetry by Jane Yolen, and revealing plenty of resonant story placements—also makes for an excellently curated reading experience, best read in the provided order. My only caveat, before I leap into high praise for the pieces themselves, is that I don’t think all of these stories reflect the anthology’s explicit mission statement. Then again, an anthology is often expected to carve out a singular role for itself in the market, and promotional material often makes sweeping claims to bring readers in. In Trenchcoats, Towers, and Trolls, the third and last in the “Punked Up Fairy Tales” series, which also includes Grimm, Grit, and Gasoline and Clockwork, Curses, and Coal, Rhonda Parrish brings together twelve cyberpunk tales in a collection that is both engrossing and thought-provoking. Edmonton, Alberta-based anthologist and author Parrish is no newcomer to the anthology game: she has edited a number of other themed collections, including one about swashbuckling cats and an “Elemental Anthologies” series.

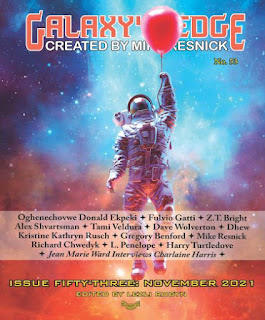

In Trenchcoats, Towers, and Trolls, the third and last in the “Punked Up Fairy Tales” series, which also includes Grimm, Grit, and Gasoline and Clockwork, Curses, and Coal, Rhonda Parrish brings together twelve cyberpunk tales in a collection that is both engrossing and thought-provoking. Edmonton, Alberta-based anthologist and author Parrish is no newcomer to the anthology game: she has edited a number of other themed collections, including one about swashbuckling cats and an “Elemental Anthologies” series. The latest Galaxy’s Edge is warmly introduced by editor Lezli Robyn, who is excited to share in this issue the winning story for The Mike Resnick Memorial Award for Best Science Fiction Short Story by a New Author. In this inaugural year for the award, the prize went to Z.T. Bright, for “The Measure of a Mother’s Love.”

The latest Galaxy’s Edge is warmly introduced by editor Lezli Robyn, who is excited to share in this issue the winning story for The Mike Resnick Memorial Award for Best Science Fiction Short Story by a New Author. In this inaugural year for the award, the prize went to Z.T. Bright, for “The Measure of a Mother’s Love.” The new novella from British Fantasy Award-nominee Simon Bestwick, out now from Hersham Horror Books, dances between urban fantasy, horror, and social commentary. The story is decidedly British, with British sensibilities and concerns that flavor the narrative throughout its brisk telling. When a story is light on plot, as it is here, success is measured by the story’s execution. Originality. Commentary. A situation that lingers with you long after you’ve finished reading. Devils of London has the pieces to be successful—timeliness, an interesting point-of-view character, high stakes—but ultimately, the execution of the story as a whole falls short of its promise.

The new novella from British Fantasy Award-nominee Simon Bestwick, out now from Hersham Horror Books, dances between urban fantasy, horror, and social commentary. The story is decidedly British, with British sensibilities and concerns that flavor the narrative throughout its brisk telling. When a story is light on plot, as it is here, success is measured by the story’s execution. Originality. Commentary. A situation that lingers with you long after you’ve finished reading. Devils of London has the pieces to be successful—timeliness, an interesting point-of-view character, high stakes—but ultimately, the execution of the story as a whole falls short of its promise.