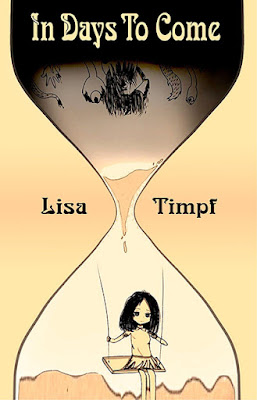

Lisa Timpf, In Days to Come. Hiraeth Books, 2022. Pp. 80. ISBN 978-1-0879-2712-1. $10.00.

Reviewed by Jason Kahler

A reader’s response to In Days to Come, Lisa Timpf’s slim collection of poetry, will depend on his or her attitude toward a few things:

A reader’s response to In Days to Come, Lisa Timpf’s slim collection of poetry, will depend on his or her attitude toward a few things:

- Poetry in general.

- Haibun specifically (more on those in a bit).

- The role of poetry in the SFFH space.

I love poetry, and I love science fiction, so I’m all for bringing the two together. Overall, readers will find plenty to enjoy in Timpf’s book. There are enough poetic moments, what noted poetry critic Clive James called “little low heavens,” to make readers feel like the time they share with the book was time well-spent. Casual or new poetry readers will enjoy finding poetry doing things they didn’t know poetry could do. More critical poetry fans will appreciate Timpf’s book, too, though they may be able to identify some places where the book’s weakest elements don’t live up to the promise of its strongest.

Timpf writes haibun, pieces that combine loosely-defined haiku with prose poetry. Most readers will recognize haiku and their familiar 5-7-5 syllabic structure, but prose poetry might be something new. I know I didn’t study prose poems in school, and while prose poetry and the haibun are both very old forms, prose poetry in particular is experiencing something of a modern re-discovery. Newly-appointed United States Poet Laureate Ada Limon has successfully worked in the form.

Timpf’s haiku don’t always follow the strict 5-7-5 structure, but the tone and physical form on the page are clear. According to the “rules” of a haibun, the haiku attached to the prose poem should further develop or comment upon the prose poem’s subject. I imagine it’s hard to write a haibun with a haiku that doesn’t feel superfluous. Like a tail on an orange. Throughout In Days to Come, Timpf uses the prose sections of poems to share a narrative—there’s always a story being told in each poem. The haiku expand on the story, and generally wouldn’t have the same impact taken alone.

For example, “When the Stars Align” tells the story of mysterious stellar gates and “They” who use them to leap across the galaxy in coal-black ships, looking for a place to lay their eggs. At the poem’s conclusion, Timpf writes,

Will it be near, or far, that time? None can

say. But when it arrives, you will know.

autumn sky—

caught in the open

nowhere to run (51)

Quoting directly from the poems won’t capture the form very well, I’m afraid, but this short snippet shows the tail end of the prose work, followed by the haiku. Without the context the prose pieces provide, the haiku wouldn’t land with any sort of meaning.

The main weakness of the collection is its overreliance on sci-fi cliches (see the black ships and the egg-laying aliens) and generic crutches. Here I admit my own poetic biases. I respond best to poems full of stuff. Tangible items that are specific and mean something. Timpf lets us fill in the blanks too much by not pushing the details toward the specific.

Take, for example, the poem “Small Mercies,” which tells the story of a war between the speaker’s people and the Hydreans. The speaker’s squad finds a wounded Hydrean soldier who they patch up, and when the alien’s people arrive, by way of evening the score, both sides walk away without fighting:

But then they notice our prisoner. They

exchanged a few words, clicking and hissing,

shooting us sidelong looks the whole time. We

didn’t share a language, but their gestures

were clear. You go your way, we go ours. And

we take him with us. I gestured back, He’s all

yours. (57)

We never learn much more about the Hydreans. They have heads, and walk stiffly or sometimes shimmy, but that’s it. They give sidelong looks, but what do their eyes look like? What sort of bodily structure do they use to click and hiss? What are they gesturing with? Arms? Legs? A tail? How many? If you’re going to have aliens, show the aliens. That’s why we buy the ticket, even if for just a little glimpse.

Sometimes the language Timpf employs pulls a reader away from the narrative. It slips into an informal voice too often, as though the voice behind the poem is in on a joke they shouldn’t understand. Prose poems can get away with a lot, but they can’t slip like “We Wish You Luck,” a piece written in the voice of a member of an omnipotent species who’s had enough our humanity’s crap:

And we tried. But as it turns out, you humans

are so—well—dense, is the best way I can put

it. Literally. We Ephemeri can pass through

walls, surf on a wave of sound, absorb the

very fabric of light. You on the other hand,

are clod-like. Earthen. (46)

That passage is an excellent example of Timpf at her best and her worst. The wordplay with “dense,” and the name of the ghost-like aliens, makes a hardened sci-fi fan roll their eyes. But the use of “clod-like,” and “Earthen”—that’s got some zing. For an alien race interrogating our lives and our language, the connection between those two words would be interesting. I find it interesting, as a reader. It’s specific. Insightful, even if the Ephemeri themselves seem a little—well—old hat.

Maybe I’m nit-picking, and maybe the audience for this book hasn’t seen and read all the egg-laying conquerors and wraithlike dream-visitors stories the genre has given us the last 70 years. That also isn’t to say that we grizzled veterans of the genre won’t find something in this book to admire. “The Horsemen Wait” has the best ending (which I won’t give away here), and the next poem in the book, “They Learned Too Well,” is a nice nod to poetry history. “Farming on Eta Four” includes an interesting list of what settlers on a new world are planting:

Beefsteak tomatoes, ideal for grilling, swell in

shades of pink; prolific cross-pollinated

spinach grows in whorls and spikes; crisp and

mild-tasting pole beans and yellow peas reach

skyward, their vines thick enough to climb. (71)

A passage like this—specific, unique, full of life and detail—stands out among a collection that resorts to too many sci-fi expectations. Beefsteak tomatoes are the most uninteresting tomatoes for us here on Earth, but it makes sense the colonists would carry such a sturdy crop. And grilling! That’s interesting! The rest of the details are excellent and evocative.

There are other moments like this—the little low heavens—that I won’t spoil. I wish there were more, or rather, I wish Timpf had taken the time to replace everything I’ve already seen before. She has a gift for building worlds in very little space. The universe is big and wonderful, and when Timpf lets us see something through her eyes that’s new, there’s plenty to please fans of both poetry and science-fiction. I look forward to seeing where Timpf can take us next.

No comments:

Post a Comment