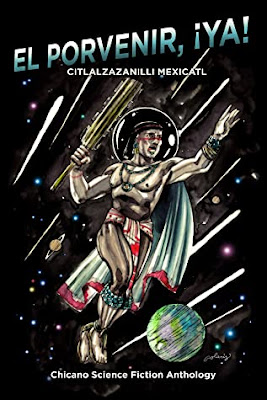

Scott Russell Duncan, Jenny Irizary & Armando Rendon (edd.), El Porvenir, ¡Ya! – Citlalzazanilli Mexicatl: Chicano Science Fiction Anthology. Somos en escrito Literary Foundation Press, 2022. Pp. 220. ISBN 979-8-40993-671-6. $10.00 pb / $2.92 e.

Reviewed by M.L. Clark

There’s a freewheeling energy to the introductions to El Porvenir, ¡Ya!, a 2022 Chicano science fiction anthology edited by Scott Russel Duncan, Armando Rendón, and Jenny Irizary. Both pieces, one by Ernest Hogan and one by Duncan(-Fernandez), proclaim with great celebratory fanfare the distinct possibilities and resurgence of the “Latinoid imagination” in contemporary science fiction. The absence of Latino rep in preceding sci-fi did not escape these editors’ notice, either, and the collection promises to introduce characters and contexts that illustrate the science-fictional nature of existence already intrinsic to many Latino communities living in blended, mestizo realities, especially in North America. How can there not be worth in celebrating, discovering, and cultivating as many of their imagined futures as possible?

There’s a freewheeling energy to the introductions to El Porvenir, ¡Ya!, a 2022 Chicano science fiction anthology edited by Scott Russel Duncan, Armando Rendón, and Jenny Irizary. Both pieces, one by Ernest Hogan and one by Duncan(-Fernandez), proclaim with great celebratory fanfare the distinct possibilities and resurgence of the “Latinoid imagination” in contemporary science fiction. The absence of Latino rep in preceding sci-fi did not escape these editors’ notice, either, and the collection promises to introduce characters and contexts that illustrate the science-fictional nature of existence already intrinsic to many Latino communities living in blended, mestizo realities, especially in North America. How can there not be worth in celebrating, discovering, and cultivating as many of their imagined futures as possible?

The collection itself is wide-ranging, as befits an attempt to get the ball rolling on bringing new voices into the fold. Some stories are goofier and looser than others, perhaps not digging as deep into their characters, themes, or settings as they could, while other stand out for their ideas and follow-through alike. For a sense of the “goofier,” the opening piece, Ernest Hogan’s “Incident in the Global Barrio,” is as lighthearted as one can get in a story about a MAGA-hat-wearing entitled white man entering a Mexican restaurant and stamping his feet at everything about the culture that makes him uncomfortable. Is it heavy-handed? Yes. But there’s an also a striking optimism to the piece, which ultimately suggests that minds can be changed, with presence and time (and of course, good food).

Conversely, Mario Acevedo’s “El Chivo” dives deep into a future world of womb-rentals that allows families to make money in a precarious economy, and also provides shifting relational dynamics within the families as different members phase in and out of becoming primary earners, or make choices that refuse the stark options presented by formal society. A nuanced what-if with a well-paced reveal of an ending.

Frank Lechuga’s “Dana” is a different beast altogether: a slice of story from the author’s larger arc, which he explains in a strongly didactic opener preceding the main action-thriller set in a martial law state, where our protagonist works security with an exceptional amount of personal power over a slice of L.A. he considers a kind of kingdom. This is more of a teaser, heavy on description of the setting and legal structures and insurgent struggles of Lechuga’s world.

“Ap-Hell” by Martin Hill Ortiz starts off a section focused more on space exploration. Here, we’re given a meditation on identity on a Mercury colony. For all the hardships of life on such a challenging planet, are there not still similarities with life on Earth? Enough to grow upon? Pedro Iniguez’s “The Facsimile War” gives us a story of a “volunteer” in the Terran Coalition Army, rematerialized after death into ongoing service for a distant colony, with no memories of the person who’d apparently signed him into this living hell, fighting vamps to save humanity. It’s classic military SF, well paced as it hurls the reader into a doomed confrontation.

Nicholas Belardes’s “Sky Seekers” drops us into deep-space action with the wounded Hirving, a bot named Mascota, and a ship about to crash on a jungle moon. But the story wanders immensely—through war, through shipyards, through an ill-fated romance, through questions of sentient AIs and the people who defend them. A ramble of a tale, not without its charms.

The next section brings us more fantastical fictions. Armando Rendón’s excerpt from the YA novel The Wizard of the Blue Hole depicts a 1950s San Antonio where an old curandero helps young Noldo recognize an evil force that is out to destroy him, and takes him through a journey of Chicano history for respite—for now—from the attacks. Lizz Huerta’s “Lorenzo and the Rooster” is a tragic love story of a dream-vision, following a man and his rooster through their twinned past lives, always connected to each other in some way through multiple reincarnations, and with Death ever watching over their intimacies and transgressions. A rich, thoughtful journey of a read.

Artwork of a male and a female figure from Obsidian and Feathers, an RPG by Emmanuel Valtierra, next presents its own dream-visions as an evocative break from the text, replete with symbolism in both the figures and their landscapes. The collection shifts to stories on longing. In Rios de la Luz’s “Lupe and Her Time Machine,” a time machine concocted from science texts, dreams, and nature blended with tech is put to one grandmother’s driven purpose: to try to break the cycles of violence and neglect and trauma in her family line. It takes a lot of ritual and work, but maybe, just maybe, a better future is still within reach.

Rosaura Sánchez’s “Road Detours” (translated by Beatrice Pita) dives into immigrant tensions in the U.S., starting with an abusive immigrant man who’s willing to throw Latina women under the bus (politically, and through domestic violence) to ingratiate himself further in the American dream. The crux of the story follows a road trip of escape and self-discovery, though, that reconnects one woman with the deeper indigenous histories of this land in which (today) she is merely “other,” an immigrant—but in which there was also, always, masculine violence to contend with, too. A time-slipping tale rich with detail, patiently told.

R.Ch. Garcia’s “Crossing the white lines on Colfax Ave” follows a returning U.S. vet’s struggle to reacclimate—which definitely isn’t easy when the world one returns to involves a gentrification unlike any other: an app and tour-based business that lets people ride into a carefully bubbled set of past moments in U.S. history. Some wild. Some dangerous. But is there anything to this venture, beyond some smug kid-programmer’s passion project and opportunistic racism and sexism? The story wanders quite a bit, and the protagonist uses a jumble of anachronistic speech, but it’s a lively enough adventure.

“The Archivist” by Richardo Tavarez takes the idea of music transporting us to another time and place to its fullest, with the story of an archivist whose experience with an LP by a singer named Carmen soon finds him transported to her era. Once he figures out the trick of the time-slip, he leans into being part of history in a whole new way.

Rosa Martha Villarreal’s “The Navel of the Aztec Moon” starts on a heavily expository note, describing a mysterious grant and an academic scientist keen on nailing the final interview to receive it. At the benefactor’s estate, Natasha is presented with the eccentric professor’s theories about ancient prophets being time-travelers, and they talk Joseph Conrad and quantum physics, Jewish and Mexican family histories, and strange events in the Valley of Mexico. It’s not your typical job interview, and all hinges on a final reveal.

The last section leans on the idea that survival stories in Chicano sci-fi and fantasy do double-duty as nonfiction, reflections of real histories of struggle. In Carmen Baca’s “They DO Exist!”, our narrator tells us about a strange encounter with a hungry fairy named Necahual (which means survival) who has a story to tell about the near-obliteration of her kind—because stories can live on even if we don’t. The tale wanders a bit, but with a heartfelt message to bring history to life at its core.

Scott Russell Duncan’s “The Return of the Notorious Pavo Loco ‘Big Boi’ Briefly Known to the Public as ‘Gerald’” then gives us a goofy story inspired by one heck of a fierce turkey. Duncan’s version of Big Boi’s adventures dips into mythology and involves the making of a Turkey Emperor, which lives for years as a bane and terror in the minds of garden gentrifiers. Gloria Delgado’s “El Parbulito” also draws from real events, in 1747 in central Mexico. Our protagonist is a humble converted “indio” working in a town where death, at least, is supposed to make equals of us all. But as high-born Don Augustín is laid to rest, our protagonist wanders through ruminations about colonization, familial suffering, plagues, and… a dreaded tale of a bloody newborn tossed at Augustín years earlier, which has haunted him ever since. The story doesn’t draw upon the supernatural except in its hope of a divine power that might also help to set this trauma right.

Lastly, Kathleen Alcalá’s “Oscar and Natalia and Oscar” (an excerpt from Los Voladores) is a tender tale about a man, a woman, and a cat, and how their lives changed after the “Big Pulse” took out all electrically dependent systems, requiring them to travel in search of a new life. It’s a story with strong echoes for many existing (and more terrifying) treks for safety, but with deep tenderness and wonder at its core—even as the journey never ends. A gentle closer to this wide-ranging anthology.

El Porvenir, ¡Ya! is a collection that prioritizes potential over consistency, so while some stories ramble and others manifest more controlled pacing and plot; while some are silly and others advance serious and potent ideas; while some lean hard into sci-fi and others into a more fluid sense of the spiritual and fantastical, all stake out a terrain of invitation: for other authors to follow after, and for future stories to build on the Chicano sci-fi that’s now, at last, more often getting noticed when it’s told.

No comments:

Post a Comment